Welcome back, readers! I have finally finished course work and comprehensive exams for my doctorate, so you should be seeing many more blog posts in the near future!

To dive back into this blog, I want to take a look at the scientific approaches to learning and their relation to music education. At the beginning of my degree at the University of Colorado, I came across Gabriele Wulf’s research in her book Attention and Motor Skill Learning. Through her research as a Professor of Kinesiology and Nutrition Sciences at UNLV, she shows the benefits of adopting an external focus of attention when learning a new motor skill. This information can be easily translated into music education!

First, it is important to recognize the steps in motor skill learning that are imperative to learning a new instrument. Example 1 shows a modified graph from Wulf’s book of R.N. Singer’s Motor Skill Learning Stages. Of course, the goal for our students is to reach the autonomous motor learning stage as quickly as possible, however, we generally begin teaching students by directing their attention on how to move their bodies. This causes them to adopt an internal focus of attention and they tend to control their movements consciously. Surprisingly, this internal focus of attention can actually have negative implications for the students as they grow and develop.

Example 1

| Stages of Learning | Characteristics | Attentional Demands |

| Cognitive (Verbal) | Movements are slow, inconsistent, and inefficient. Considerable cognitive activity is required | Large parts of the movement are controlled consciously. |

| Associative | Movements are more fluid, reliable, and efficient. Less cognitive activity is required. | Some parts of the movement are controlled consciously, some automatically. |

| Autonomous (motor) | Movements are accurate, consistent, and efficient. Little to no cognitive activity is required | Movement is largely controlled automatically. |

The Research

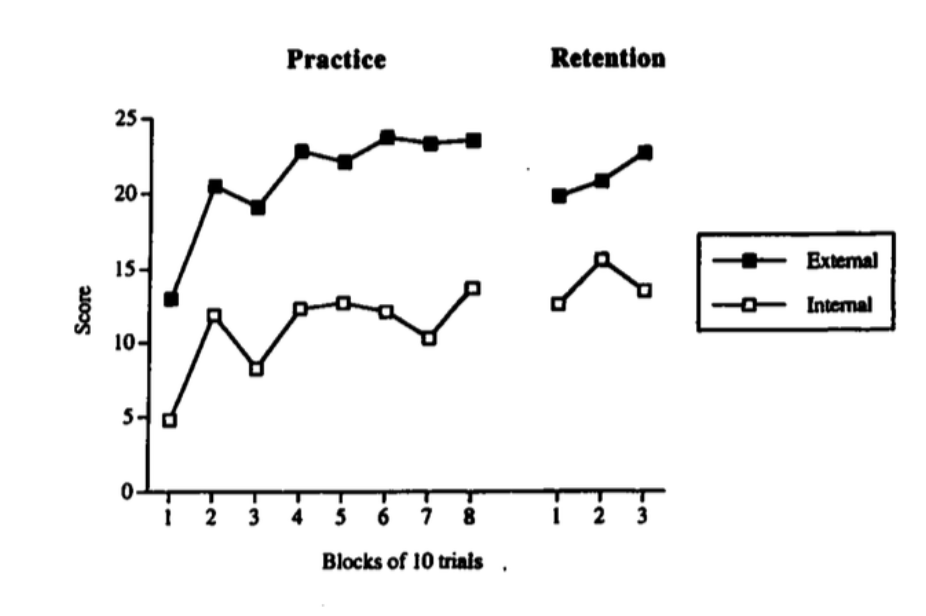

To prove this point, a study was completed in 1999 by Wulf, Lauterbach, & Toole that showed that the performance of beginners can actually suffer when they are given internal instructions about correct technique. In this experiment, individuals who had no prior experience with golf were employed with the goal of hitting a golf ball closest to the center of the circle. There were four different zones around the circle and the closest zone received four points, with decreasing point values the further away the ball was from the target. Therefore, the objective was to get a higher score. One group in this experiment was given the internal focus directive to focus on the swing of their hands and the other group was given the external focus directive of focusing on the swing of the club. The results of this experiment are shown in Example 2.

As you can see, the external focus group far outperformed the internal focus group. This is just one of the many experiments that shows the positive impact that utilizing an external focus of attention can have on student learning.

Example 2

Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Vol. 70, pgs. 120-126, Copyright 1999 by the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance

Why does this happen? If a student adopts an internal focus of attention, they tend to subconsciously intervene in the control processes that regulate the coordination of their movements. This disrupts the automatic control that was evident in the third “autonomous” learning stage. On the other hand, if they focus on the movement effect (external focus), it promotes the automatic control that reduces conscious interference and enhances learning.

How can we translate these findings for music education and focus on the movement affect? The answer to this question is simple and we should be encouraging our students to remain focused on the sound that they are producing. A common example of internal focus directives that are given to a young brass player is teaching them how to form an embouchure, eg. “flat chin, corners in.” While this may produce quick results, the student will likely be using far too much tension and the sound that they are producing can be strained and tight.

Another approach to teaching a brass student using an external focus directive would be to “expect” sound out the bell of the horn. While this may seem like a very “new age” concept, this places the student’s attention on the sound that they want to produce, rather than on how to manipulate their body to create the sound. This approach requires a great deal of experimentation for the student and will likely take longer to accomplish. As an educator, you can encourage the student to expect sound out the bell of the instrument by introducing concepts that are already familiar to them and gradually integrating the “unfamiliar” instrument. This can be done first with the blow. Using a coffee straw that is placed just outside the lips, demonstrate blowing air through the straw. The goal of the coffee straw is not air speed, however, it is being able to blow air to the other side of the straw with a relaxed airstream. After the student is able to accomplish the relaxed airstream with the straw, have them do the same thing by blowing relaxed air out of the mouthpiece. Keep in mind, this is only air and not creating a buzz. After both of these tasks are accomplished, introduce the instrument with the same goal of relaxed air out the bell of the horn. Through this scaffolding process, you have gradually brought the attention of the student to the movement effect, which is relaxed air through the instrument. Since their attention is already at the bell of the instrument, they can now begin experimenting on creating sound. This is just one of many methods that we can use to encourage our students to learn more effectively. Of course, this does not mean you can only teach with external focus directives and it is important to find a balance of both internal and external instructions.

Additional Examples of Internal vs. External Focus Directives

| Goal | Internal | External |

| Right-Hand Position | Curve your right hand and place it in the bell with the top of the thumb bearing the weight of the horn. | Cup your hand like you are scooping water from a river and place at the 1 o’clock position in the bell. |

| Playing a Lip Trill | Adjust the inner diameter of your aperture by making minor changes to the air speed using the support from your diaphragm. PSA: The diaphragm is an involuntary muscle that cannot be consciously controlled. |

Expect the sound of the trill and spin your air forward to teeter between the two notes like you are balancing on two sides of a fence post. |

| Playing Stopped Horn | Use your hand to cover the entire opening of the bell and “blow” harder. | Squeeze the horn, like an accordion to cover the opening of the bell, and imagine the sound that you want to produce. |

References

Wulf, Gabriele. Attention and Motor Skill Learning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007.

Wulf, Gabriele, Barbara Lauterbach, and Tonya Toole. “The Learning Advantages of an External Focus of Attention in Golf.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport70, no. 2 (1999): 120-26. doi:10.1080/02701367.1999.10608029.